The Credentialling Sector has been taking some hits lately; people have started to ask whether that sheepskin is really worth what you pay for it. But the credential police have a crack defense team,

including the New York Times, in the person of David Leonhardt:

ALMOST a century ago, the United States decided to make high school nearly universal. Around the same time, much of Europe decided that universal high school was a waste. Not everybody, European intellectuals argued, should go to high school.

It’s clear who made the right decision. The educated American masses helped create the American century...The new ranks of high school graduates made factories more efficient and new industries possible.

That's pretty breathtaking, isn't it? A hundred years of bloody history, and it all comes down

to mandatory schooling. The Battle of the Bulge was won on the gym floor of East Bumfuck High School -- never mind where Vietnam and Afghanistan were lost. And the "American Century", forsooth! Was ever a richer lode of mindless cliche struck than the New York Times?

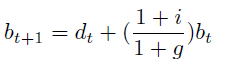

The rest of Leonhardt's piece is equally slapdash. For example, he says, "A new study even shows that a bachelor’s degree pays off for jobs that don’t require one: secretaries, plumbers and cashiers." In a subsequent column, he backs this up with a graph, also attributed to what is apparently the same Georgetown U report:

Unfortunately, the links he provides don't lead to this info, as far as I can tell, much less to any indication of how these statistics were derived. The Georgetown report itself says, in its introduction:

When considering the question

of whether earning a college

degree is worth the investment

in these uncertain economic

times, here is a number to

keep in mind:

84 percent.

On average, that is how much more money

a full-time, full-year worker with a Bachelor’s

degree can expect to earn over a lifetime than

a colleague who has no better than a high

school diploma.

But the Georgetown savants don't tell us what kind of "average" this is (mean or median? It makes a difference) or how the number was calculated. (The Georgetown report does contain some unsurprising and no doubt accurate information -- a major in petroleum engineering is worth more than a major in social work; stop the presses.)

Still, let's assume, arguendo, that it's all more or less true; that college graduates are either more likely to be hired, or to be paid more after they're hired, than non-graduates. It doesn't seem unlikely. We might quibble about the precise numbers, and will certainly quarrel about the precise mechanisms that explain the effect. But the effect, such as it is, seems consistent with everyday experience.

The bigger question, of course, is, What are the implications? For the credentialling sector's defense team, the answer is self-evident: all the people who don't now go to college should go to college. Presumably then everybody's income would be up at the BAs' level, right?

Well, wrong, of course. I call this the Bus Fallacy: Anybody can get on a city bus, but everybody cannot get on a city bus. A city bus isn't big enough for everybody.

There are a good many lemmata to this insight. A lot of bubbles are blown up with exhaust gas from the Bus Fallacy. Anybody can make money speculating in real estate; but if everybody expects to make money speculating in real estate, who are they going to make it from?

You get the idea.

The BA confers an advantage. Okay. But an advantage ceases to be an advantage if everybody has it. It's a little like the atom bomb that way.

The credentialling bubble, I think, is nearing the point of collapse, like the dot-com bubble and the real-estate bubble of recent memory, and the locus-classicus South Sea and tulip-bulb bubbles of more venerable memory.

Every college campus I've been on in the last ten years is frantically building new towers and dorms and Centers for This Studies and That Studies -- and above all, gorgeous "fitness" centers, staggeringly lavish and Sybaritic, stocked with hundreds of gleaming exotic exercise machines. I daresay there is no muscle in your body, however small or obscure, that doesn't have a machine specifically designed to exercise it; and the Unis, who presumably know their demo, are buying 'em by the bargeload.

Counsel for the Defense Leonhardt acknowledges that

the [college-noncollege] income gap isn’t rising as fast as it once was, especially for college graduates who don’t get an advanced degree

-- though amusingly, he doesn't provide a link to any "study" that explores this interesting fact. But it's consistent with the overstretched bubble theory -- as is the fact that advantage is now migrating from the BA to the "advanced degree". As the advantage of the BA diminishes, some other advantage must be found, and some other after that....

The real, interesting question is, why this preference for the accumulation of sheepskins on the part of the employer?

With petroleum engineering you can see it, or indeed with any job that requires a very specific set of skills. The employer would obviously prefer that the employee train himself, at his own expense, rather than expend the money to train him. And the more of these costs that the employer can offload -- if he can demand advanced-degree training rather than BA training, say -- the better the bargain for the employer. It's like expecting an employee to have his own tools or use his own car on the job.

Of course if you look at this phenomenon from a certain angle -- the angle I prefer, as a matter of fact -- then the demand for credentials looks like one means (among many) of exploitation. In effect the employer requires that the employee defray ahead of time what would necessarily otherwise be a capital expenditure on the employer's part; this pay-in on the employee's part becomes a precondition to entering the sweatshop door and being exploited further. The pay-in is so valuable to the employer that he might actually let up slightly on the back-end exploitation, and purely as a business proposition, this may in some cases work out to the employee's net lifetime balance-sheet benefit too, at least as compared with less fortunate or astute wage-slaves.

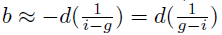

But here again we encounter the Bus Fallacy. It might work out for any given employee; but it can't work out for every employee. If you look at it group-wise, then it's a net loss for the employee group overall. The more capital expenditure the employer group as a whole can offload onto the employee group as a whole, the worse off the latter group is. That's just arithmetic.

Of course there will always be some individuals, perhaps a good many, who beat the odds,

as in the real-estate bubble -- people who bought at the right time and sold at the right time.

But for every win there's a necessary loss.

Unless I'm committing a Lump Of Something fallacy here? These lump fallacies have been much discussed on this blog and its linksisters of late. Suppose that if everybody got a BA, the world would change in wonderful and unpredictable ways? I guess we can't rule it out; but we can hardly depend on it either.

What's even more interesting than the straightforward petroleum-engineer effect is Leonhardt's argument that a degree brings the employee more money even if his studies were utterly irrelevant to his job. If there's really anything to that -- if we accept the implications of Leonhardt's poorly-sourced chart -- then some explanation is called for. Speculation on this topic might require another post. Leonhardt seems to think it's all about the character-building and mental-workout aspects of college.

Humph. From what I've seen of college, I doubt it.

I have an exceedingly low regard for Aussienomics, and I hope you all do

too!

I have an exceedingly low regard for Aussienomics, and I hope you all do

too!